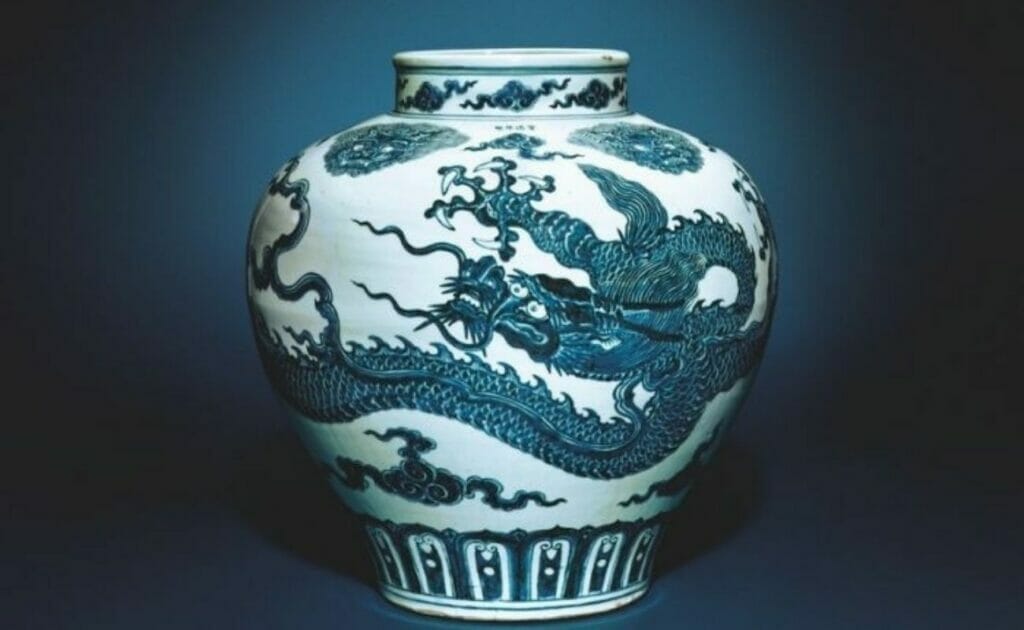

Few objects in the world are so famous that they are known by their place of origin. Like Champagne, Damascus steel and limousines, Chinese porcelain joined the ranks of eponyms when the English-speaking world came to call it ‘china’. And from this transliteration sprang another curious figure of speech: the Ming vase.

This is fascinating for two reasons. Firstly, the Ming dynasty refined ceramic development. But it was the improved enamel glazes of the early Qing dynasty, fired at a higher temperature, that acquired a more brilliant look than those of the Ming dynasty. Secondly, blue and white porcelain – the kind we’re most familiar with – wasn’t even a Ming invention.

It first appeared in the earlier Tang and Song dynasties. So, Ming porcelain was neither the first nor the best, but it remains one of the most significant milestones in ceramic history because it was during this dynasty (1368-1644) that China dramatically improved its ceramic technology. The imperial court developed a taste for more vibrant colour schemes, and overall economic prosperity meant a greater demand for beautiful homeware. Foreign trade was also at an all-time high, leading to the reputation of China’s beautiful porcelain spreading far and wide.

“Ming porcelain is neither the first nor the best, but it remains one of the most significant milestones in ceramic history.”

The Ming’s porcelain prowess had so exceeded the quality of its predecessors that the Ming dynasty’s Yongle Emperor ordered the construction of a pagoda with white porcelain bricks in his capital city of Nanjing sometime during the 15th century. The Porcelain Tower of Nanjing became one of the seven wonders of the medieval world. A modern replica still exists today.

The Ming dynasty’s achievements were many, including the building of the Forbidden City and the majority of the Great Wall, advancing printing methods and maintaining the largest economy in the world. But for most, it’s the breathtaking work of the era’s best porcelain craftsmen that define the period. And who can fault them?

The Ming Vase

This treasured piece of porcelain has become a figure of speech in the English language, inspiring ideas associated with fragility, preciousness and antiquity. But why the Ming dynasty and why a vase? We established that the real porcelain dynasty was the Qing, and demand for the beautiful and delicate Qing wares in the West soared. Under the reign of the Qing’s Kangxi Emperor (1662-1722), porcelain flooded the European market. Interestingly, Ming porcelain, which wasn’t far behind in terms of quality, was therefore considered rarer and seen as more exotic. The vase imagery is a logical one. A vase is functional enough to find a place in most households, especially moneyed ones. It is also large enough to show off the artistry of ceramic decoration. Size doesn’t always matter, though. The record holder for the highest price paid for a Ming dynasty piece is the Meiyintang ‘Chicken Cup’, a small porcelain cup painted with chicken motifs that sold for HKD281.24 million at Sotheby’s in 2014.

Signature work

It was only during the Ming period that the practice of adding reign marks or dates to ceramics became commonplace. They consisted of six characters read vertically from right to left, with the first two characters spelling out the dynasty and the next two stating the title of the current emperor. The final two were usually nian zhe (made for). The most common examples featured these marks written in underglaze blue and ringed by a double circle found at the base or mouth of a vessel.

Fakes abound, but take note that some reign marks claiming to be from an older period than the ceramic itself may not be outright forgeries. There were artisans who copied these reign marks out of respect and reverence for those earlier periods, and you’ll find them classified as ‘apocryphal marks’ in auction catalogues. While the quality eventually suffered as quantities went up in response to increased demand both locally and from abroad, Jingdezhen is easily the world’s most famous porcelain capital. It is currently home to the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum, which houses 19,000 ceramic articles.

Evolution of Ming design

Great art is never static. Here’s a broad outline of how designs took on the tastes of the times.

A vase from the early Ming period

Statue of the goddess Guanyin in all-white ceramic

It was during the reign of the Yongle Emperor that the fragile eggshell porcelain style emerged

As porcelain became a significant export to Japan and Europe, its decoration became increasingly more extravagant

Early Ming period

Blue and white porcelain, now practically the archetypal icon of Chinese porcelain, really took off in development and sophistication during the Mongol-ruled Yuan dynasty and was still highly prized – even after the transition into the Ming period. Understandably, the Ming’s first emperor, Hongwu, wanted few reminders of the country’s former foreign overlords, and so did not adopt this type of porcelain in court.

He ordered his wares to be monochrome red. These were difficult to execute, and few pieces exist today. Outside the court, blue and white porcelain was in high demand, and Arab clients requested for intricate, abstract and floral decorations that were similar to their textiles back home. As the century progressed, designs became more restrained and delicate to suit Chinese sensibilities and moved towards birds, flowers and landscapes.

15th century CE

Stylistically, this was, generally speaking, an era of restraint. The motifs were often of birds and flowers with a lot of white space. Speaking of white porcelain, another famous porcelain-producing town, Dehua in Fujian province, became famous for its all-white ceramics. These undecorated pieces would earn the name ‘blanc de chine’ in the West and become sought after for its thick, lustrous glaze and sometimes milky ivory hues.

Overglaze painting of Dehua’s white porcelain was unusual, and those that had been embellished were usually done in Europe. The most common examples in China, however, were pure white figures and statues of the goddess Guanyin.

Yongle and Xuande reign

Details are fuzzy on when precisely cloisonne enamelling made it to China, but records hint at this being another Islamic import during the Yuan dynasty. This decorative technique, which involves filling cells made of wires with coloured enamel, was, and still is, colourful and elaborate – and considered more suited to temples and palaces. The Ming’s Xuande Emperor was especially enamoured of these.

It was also during the Yongle reign that another style emerged: fragile eggshell porcelain, characterised by its extreme thinness. The most mesmerising had decorations engraved on them before firing that only became visible when held against a light.

16th century and Jiajing’s reign

By this point, porcelain had become a significant export to countries like Japan and Europe, and this could be one of the reasons why porcelain decoration became more extravagant. The Jiajing Emperor was the first to start commissioning the five-colour Wucai decoration that remained popular during Longqing and Wanli’s reigns. The underglaze blue enamel here was darker to complement the red, green and yellow mostly found on Wucai pottery (the fifth colour being the porcelain’s white body).

Despite its name, the Wucai style isn’t strictly limited to just five colours. On a somewhat tangential note, the combination of red and yellow in porcelain was also distinctive of this period. Much rarer during this time was the experimentation with enamelling directly onto unglazed porcelain, a practice later perfected during the Qing dynasty.

This story first appeared in The Peak Singapore