When you wear a Richard Mille watch, people notice.†This was what watch fan and Richard Mille RM11 chronograph owner, Dr Calvin Chan, told us during a recent quick chat. That’s for sure. The brand’s timepieces bear distinctive characteristics such as a tonneau-shaped case, architectural movement and dial structure, and innovative, often exceptionally light materials. Coupled with the brand’s associations with sports stars such as tennis player Rafael Nadal and Formula One driver Felipe Massa, the brand’s offerings have found favour with some of the most flush of watch collectors. Prices start at over MYR220,000 (for an RM11 women’s automatic watch) and go into the millions.

FORTY GRAMS That’s the incredible weight of the RM 50-03 McLaren F1, which contains the new carbon-based material graphene.

In a recent interview with the brand’s eponymous founder, The New York Times noted that Richard Mille had produced 3,200 watches in 2015, a figure that had grown to 3,500 in 2016 and was expected to reach 4,000 this year. In 2016, revealed Mille himself, his company’s exports from Switzerland totalled around USD270 million (MYR1.15 billion) – a growth of 20 per cent from the previous year.

In spite of – or perhaps, because of – its popularity, the brand has its fair share of detractors, who baulk at the prices that Richard Mille watches command. Typically, they question how these watches have such eye-watering price tags despite bearing no precious metals, how their movements are made by other companies, and how the nearly 20-year-old brand doesn’t have much by way of a heritage. But at a time when many traditional fine-watch companies are faltering, perhaps Richard Mille is exactly the kind of disruptive force this industry needs – a notion that was reinforced after The Peak visited its facilities in Switzerland earlier this year.

MODERNITY AMID TRADITION

Like many of its more traditional counterparts, Richard Mille is located in a quietly picturesque Swiss town in the Jura canton, where we arrived after motoring for more than an hour from Geneva. In Les Breuleux, there are two key Richard Mille facilities located a few minutes’ drive away from each other: one is Montres Valgine, where watches are assembled and serviced, and the other is Pro Art, the brand’s casemaking factory.

Along with a handful of other watch journalists, we started our tour at Pro Art, guided by the company’s spokesman, Theodore Diehl. Diehl did most of the brand’s media presentations at the Salon International de la Haute Horlogerie (SIHH) in Geneva and, just days before, had stunned a roomful of us by flinging the brand’s latest million-dollar novelty, the ultra-light RM 50-03 split-seconds chronograph, across the room to demonstrate its shock-resistance.

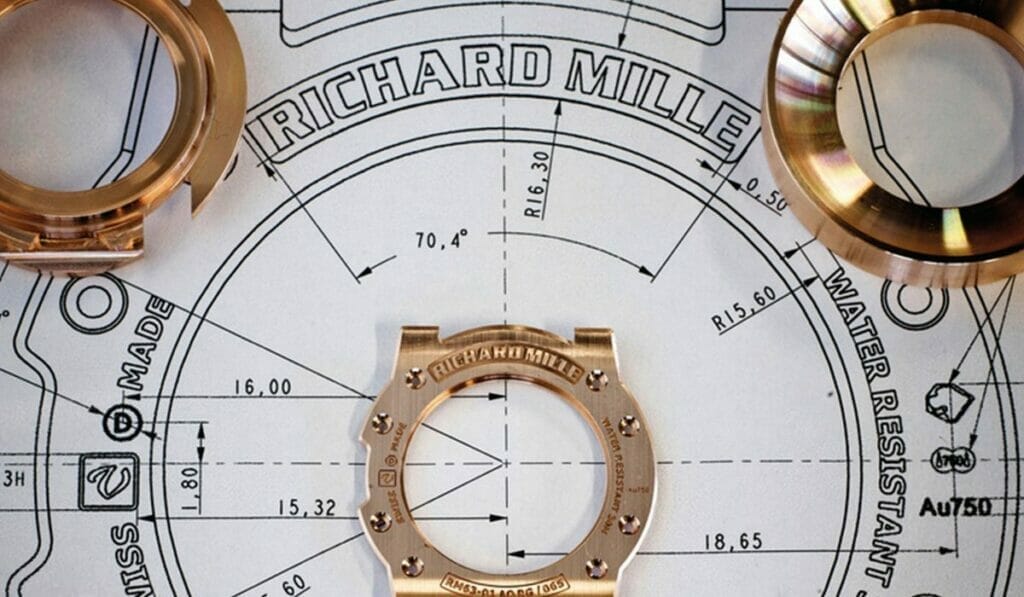

That day, the 3,320 sq m Pro Art facility was rather quiet, with some employees away at SIHH. Usually, about 50 people work in this factory, which makes the components used in Richard Mille’s three-part curved cases, as well as movement parts such as baseplates and bridges. This in itself already sets the brand apart, since few watch companies make their own cases. Instead, many rely on third-party companies such as Donze-Baume, which used to make Richard Mille cases, until it was purchased by the Richemont group in 2007. While there was a five-year grace period during which Donze-Baume continued to make Richard Mille cases, the abrupt move also served as an impetus for Richard Mille to start its own factory capable of transforming cutting-edge materials into complex cases.

NICE CURVES Whether tonneau, round or rectangular in shape, Richard Mille cases have a curvature that makes them a challenge to machine.

Said Diehl: “It was a shock for us, but it was also a godsend. Now, we can literally walk down the street (from our Valgine office), and say, ‘We have this new material – such as Carbon TPT from an Alinghi boat mast – let’s see what we can do with it.’â€

One of the high-tech materials favoured by Richard Mille, Carbon TPT is produced by Swiss-based company North Thin Ply Technology, which worked with Pro Art to perfect a version ideal for high-performance timepieces. Comprising more than 600 layers of carbon fibres compressed together at varying angles at high pressure, the carbon-based material is light while being incredibly tough and scratch-proof. While the material is produced by North Thin Ply Technology, it is machined and finished at Pro Art.

PURE POWER The Pro Art facility is the first in the Jura canton built to utilise geothermal heating and cooling systems.

The use of such advanced materials requires many adaptations on the part of both man and machine: Numerous hours are needed to programme the software that controls the CNC (computer numerical control) milling machines, and to develop suitable cutting tools that can stand up to those materials.

Diehl explained: “ TPT is harder to work with than a material like titanium and wears down the tools faster.†At this point, we peered into a large multi-axis CNC machine, which Diehl lovingly described as the “magic baby in our factoryâ€. Some 40 small blocks of different material, including Carbon TPT and Quartz TPT (another exclusive material comprising carbon fibres and quartz filaments), are positioned within the machine, awaiting specially customised and programmed tools to pick them up and work on them in different planes.

CASE BY CASE Carbon TPT case parts at various stages of completion.

It’s a lengthy process, considering that even the brand’s “standard†titanium cases take about a week to complete, not least because the three parts of each curved case (front bezel, caseband and back bezel) must fit together precisely, and certain materials warp when milled into a curved form. Creating the titanium case of the brand’s latest flagship model, the RM 11-03 flyback chronograph, requires more than 255 tooling operations and more than 15 hours of finishing. In fact, just machining the relief logo on the back of a curved case takes 45 minutes.

Despite taking pride in these state-of-the-art machines, Diehl said: “I hate it when someone says, ‘Oh, they just put the parts into the machine and it comes out.’ That’s not the way it is at all.†Components produced are hand-finished and checked by trained craftspeople. Touring the premises, we saw people working on various parts: At one station, an employee was buffing a caseband on a buffing wheel, occasionally stopping to examine his work. At another, an older gentleman worked on individual bracelet links, polishing them and getting up ever so often to spray more protective coating on them. Elsewhere in the facility, a younger employee wearing silver hoop earrings and a black hoodie carefully eyeballed a piece of curved sapphire glass through his magnifying loupe, occasionally scrubbing at smudges invisible to us.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

After a lunch break, we headed over to the brand’s other facility, Montres Valgine, where movements are assembled, cased and tested. Richard Mille and its long-time suppliers typically have co-ownership arrangements: For instance, the former has shares in Valgine, a third-party supplier that also produces parts or watches for other brands.

MAN AND MACHINE High-tech machines go hand in hand with skilled craftsmanship.

Coated employees sat at their workstations, putting together movements. We watched a lightly bearded watchmaker as he worked deftly, using a pair of tweezers to pick up components while assembling the movement of an RM 37 time-and-date women’s watch.

This brings us to another contentious point. The RM37 features a movement developed in-house by Richard Mille, but produced externally.

Such movements are an exception for the brand, which typically works with movement-making partners such as Vaucher (on simpler automatic and chronograph movements) and Audemars Piguet Renaud et Papi (APRP; for more “extreme†movements, such as a tourbillon movement with a g-force sensor) – an arrangement that some criticise, in view of the halo traditionally surrounding in-house movements.

“We are very open about our partners,†declared Diehl, adding: “The Swiss watch industry has always worked on the principle of specialisation – in the past, you would have a valley where everyone did jewels, and not a whole watch.â€

MICRO VIEW Watchmakers at Valgine are capable of assembling movements of varying levels of complexity.

We did not argue with that, especially since Richard Mille movements tend to be collaborative efforts with their own character.

Among the almost-completed watches that Diehl showed us was the RM 50-02 ACJ, an aircraft-inspired watch created in partnership with Airbus Corporate Jets. It is powered by a complex movement built by APRP – but has an aesthetic that is distinctly Richard Mille: highly skeletonised, with a multi-level construction, and a clean, almost industrial finishing.

As we wrapped up our visit, our attention was caught by a Richard Mille watch. No, not one of the many being assembled, but one on the wrist of an employee.

Affirming Dr Calvin Chan’s statement at the beginning of this story about how these timepieces do not go unnoticed when worn, we immediately registered the RM 10 automatic skeleton watch that was sported by a bespectacled, auburn-haired lady. She was placing screws into the case of a diamond-studded watch. Employees here, apparently, receive a watch after a decade of service (now, that’s a long-service award).

Despite her limited grasp of English, the native French speaker expressed herself clearly enough when we approached her and made approving gestures at her timepiece. With a smile, she told us proudly: “It’s mine.â€