It’s no secret that post-war Japanese photography in the 1960s and 70s introduced some of the most innovative camera work as seen through the lenses of Shomei Tomatsu, Kikuji Kawada and Eikoh Hosoe. However, it’s the are-bureboke or ‘rough, blurred, out of focus’ aesthetic of Daido Moriyama that came to define the era’s movement in avant-garde photography.

Though his name is uttered with utmost respect amongst patrons of the art in international circles, the formulation and exploration of his photographic language remains somewhat of a mystery to the fledgling art scene in South-East Asia – a lapse that A+ Works of Art gallery in Kuala Lumpur seeks to rectify by presenting 38 photographic prints signed by Moriyama himself.

Stray Dog, 1971.

From the series Light and Shadow, 1982.

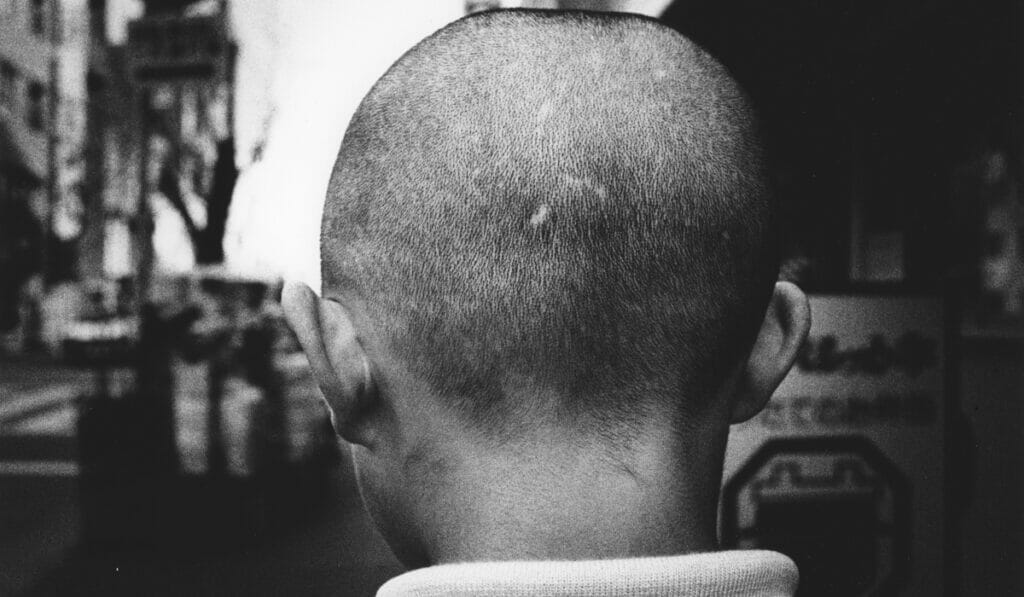

From the series Hunter, 1972.

Since 1961, the master photographer has been capturing the world through his camera lens and an encounter with William Klein’s works in New York (1956) led him to his signature exploration of the city that continues to this very day. In his 2015 publication, Dog and Mesh Tights, he says: “Like a crow scavenging the streets for food, I have captured numerous images of towns and cities, irrespective of whether they are located in Japan or abroad. It goes without saying that virtually my whole life has been devoted to the taking of photographs. No matter in what city or what country I happen to find myself, the outside world I observe as I wander the streets present me with the exciting, the mysterious or the erotic; my eyes roam freely over these sights and I release the shutter whenever I feel the urges of eternal desire or temptation.â€

His fondness for walking the streets and documenting urban life through the camera lens naturally led to referrals as a street photographer. While it may be technically true, Gwen Lee, Director of DECK, an independent art space in Singapore, who curated the exhibition, believes there’s more to it. “The title street photographer creates the image of someone who simply walks along streets and takes pictures of whatever he or she stumble across. Yes, that is the process. But there is a deeper philosophy behind Moriyama’s photography. For him, going out to the streets is to experience the city.†According to Lee, one must first understand that his works have no linear narrative nor a subject matter – his photography pursues the life and spirit of the moment. “Can one photograph really tell what, exactly, is a city? Through the images, it gives an outline of what a city might be like, essentially mapping a city, showing the sounds, seduction, ugliness and charm. This is what he points to in his photography.â€

From left: Gwen Lee, Curator of Daido Moriyama: Mapping City with Sohey Moriyama, Managing Director of Daido Moriyama Foundation.

Indeed, Moriyama himself has said that he had spent his life using a camera to create a photographic city. Again, in Dog and Mesh Tights, he admits to building this city of his own understanding – a mundane world overflowing with a confusing interaction of people and things – by capturing details of various urban centres across the globe. “In a way, it resembles a jigsaw puzzle, but unlike a jigsaw puzzle, there is no limit to the number of pieces it contains and no matter how many photographs I take, it will never be complete. Therefore, I have no option but to continue to photograph on a daily basis, adding as many pieces as possible to this unfinished, virtual city.â€

A brief glance at his work reveals another similarity beyond the arebure- boke characteristics – a distinct lack of colour. “Photography has to be black and white,†he once declared and, when prodded, simply states that he likes it and “because it looks sexyâ€. Sensuality is another distinguishing feature of Moriyama’s imagery: his early works as seen in Japan: A Photo Theater (1968) depict the seedy underbelly of Tokyo in the capital’s most infamous entertainment venues that often find patronage from artists, prostitutes and yakuzas. This stark depiction of reality follows through in his status-cementing work for Provoke magazine (published through 1968 and 1969) and subsequent publications of Farewell Photography (1972) and Tights (1987).

Naturally, one would be keen to know the inner workings of Moriyama’s avant-garde mind, but Sohey Moriyama, Managing Director of Daido Moriyama Foundation (and his nephew), reveals that the man works in a surprisingly simple manner. “He doesn’t have any fixed concept of what he wants in his pictures. To him, photography is the freedom to do anything and every picture is equally important.â€

“My photographs are records of my life,†says Daido Moriyama and, at 78 years old, the camera is still firmly clasped in his hands as he ventures out to observe the ever-expanding concrete jungles. The godfather of Japanese street photography is not done yet and the world awaits his next barrier-breaking work with bated breath.