At Bodega Delgado Zuleta in Sanlucar de Barrameda, Spain, master sherry maker Pelayo Garcia takes samples of liquid from wooden barrels with a venencia – a small cup on a long stick. He pours the golden liquid into glasses, and we drink. There are delicious hints of nuts and citrus on the nose, and it’s dry, but soft on the palate, with an elegant salinity and complexity. It’s a young Manzanilla that will eventually, after at least 30 years of nurturing, mature into Delgado Zuleta’s speciality, the Quo Vadis? Amontillado.

The bodega’s Quo Vadis? and other refined sherries, such as its flagship La Goya and its groundbreaking organic Manzanilla, called Entusiastico, are helping to elevate the status of Spain’s unique fortified wines around the world. In recent decades, sherry has been unfairly saddled with the reputation of being one of those sweet, syrupy drinks grandmothers bring forth from rarely accessed liquor cabinets on special occasions. But there are actually 10 types of sherry: five dry and five sweet. Fino, Manzanilla, Oloroso, Amontillado, and Palo Cortado are dry, while Pedro Ximenez, Moscatel, Pale Cream, Medium Cream, and Cream (the latter three being blends) are sweet.

Adding dry sherry to a Mabel’s treacle cocktail

The thirst for premium varieties of sherry, especially drier ones, but also particularly Pedro Ximenez, is growing.

“Global sherry sales may be down, with supermarket sales declining, but we’ve seen impressive demand for our premium sherries,†says Garcia. “The sherry revival in the ultra-premium category started taking off about six years ago.â€

Delgado Zuleta, which dates back to 1744 and claims to be Spain’s oldest sherry bodega, isn’t the only sherry producer seeing interest sparking in high-quality sherries.

GLOBAL REVIVAL

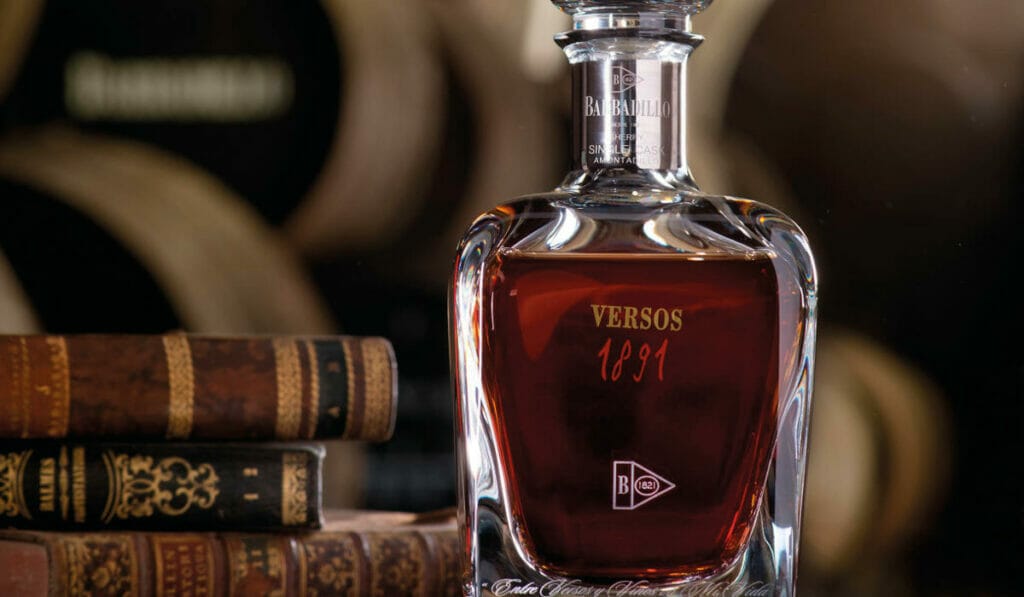

“We’re beyond the ‘granny’ image within our growing target market of wine cognoscenti,†says Tim Holt of Bodegas Barbadillo, an innovative bodega that is about to release a Manzanilla-based vermouth. It is also known for its centenary single cask Amontillado, Versos 1891 – of which only 100 bottles were produced, priced at about GPB8,000 each. “There’s a growing trend in hipster quarters in London and New York to drink sherry and use it in cocktails.â€

Versos 1891 – only 100 bottles were produced, priced at about GPB8,000 each.

London’s Drakes Tabanco is one such venue. Along with a carefully selected list of bottled sherries, the bar also brings in sherry directly from Bodegas Rey Fernando de Castilla in Jerez. The sherry, nurtured for up to 30 years at the bodega, is put into specially made antique wooden barrels at the tabanco (bar or tavern). Served unfiltered, straight from the barrel, alongside slices of Spain’s beloved jamon de bellota (ham from free-range pigs that eat only acorns), tasting sherry here is as close to the experience of actually being at a bodega as you are likely to find outside of Spain.

But it’s not only Europe and America that are showing a growing appreciation for sherry. Sales in China, especially in Shanghai, are showing growth too, just as they are in Hong Kong. Japan is also booming: “It’s where we sell the most sherry in Asia, again very much premium and above all Manzanilla, such as our Solear Manzanilla,†says Holt.

Singapore has its own fledgling sherry culture. D. Bespoke at Bukit Pasoh Road, for example, has been quietly bringing the sherry revival home since 2014. The Ginza-style bar’s noteworthy collection includes a 30-year-old Barbadillo Amontillado, and Valdespino Moscatel Toneles, probably the oldest Moscatel on the market at 80 to 100 years old. Only 100 bottles of the Moscatel are extracted each year from a single cask.

Daiki Kanetaka, who is a certified venenciador – someone skilled at taking samples of sherry from a cask with a venencia – heads the bar and says interest in sherry is increasing.

“When we interact with our customers and propose sherry recommendations now, the drinkers are definitely more savvy compared to when we opened,†he says.

TRICKLE-DOWN EFFECT

What drives those working in the bar and restaurant business to be so passionate about sherry is its history, uniqueness and variety.

“Sherry is a unique style of wine in the way that it’s aged,†says Kanetaka. “The flavours that the solera process creates are as varied as they are unique, and they can match with most meals or be simply enjoyed on their own. How this variety can come from just a few grape varieties is amazing to me.â€

The 10 types of sherry are all made from three varieties of white grape: Palomino Fino for dry sherries, and Pedro Ximenez and Moscatel for sweet versions. Like Palomino Fino, Pedro Ximenez and Moscatel grapes are sour when picked, but they are sun-dried to concentrate the sugars, then dry-pressed.

To make sherry, the must – freshly crushed grape juices – is first fermented. Musts of Palomino grapes ferment until nearly all the sugars are turned into alcohol, while Pedro Ximenez and Moscatel musts are cut off early in the process to retain sugars. At the end of fermentation, a layer of flor – natural yeast – forms on top of these base wines.

The finest, most delicate base wines then go for biological ageing – that is, naturally under the layer of flor, without contact with oxygen. They make the driest sherries, Fino or Manzanilla. The rest will be fortified to about 17 per cent alcohol volume to kill the flor, leaving the wine to oxidise – mature in contact with air – like regular wines. Naturally sweet wines are always fortified to a higher alcohol content to remove the flor.

The base wines are then classified again and put into a solera system – a stack of casks with the youngest wines at the top gradually replacing the older, more mature wines in the bottom row of casks. As older wine is taken out, younger wine is added; some solera systems therefore have traces of sherry that are as much as 100 years old. Sherry must, by Spanish law, be aged at least two years to develop the distinctive characteristics of each type.

A TASTE OF GEOGRAPHY

All wine labelled as ‘sherry’ must also come from the Sherry Triangle, an area in the province of Cadiz in Andalusia between Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlucar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa Maria. The word ‘sherry’ is an anglicisation of Xeres (Jerez).

Sherries are classified as Jerez- Xeres-Sherry DO, the DO standing for Denominacion de Origen which, similar to the French ‘appellation’, is a Spanish classification system to regulate quality and geographical origin. Manzanilla, which is essentially a Fino but made in Sanlucar de Barrameda, actually has its own certification, DO Manzanilla- Sanlucar de Barrameda, but is commonly referred to as a sherry.

As with wine, terroir is crucial to sherry. This part of Spain is unique in its geography, climate and environment. Jerez is hot and dry in summer, and as no irrigation is permitted in the DO of Jerez-Xeres- Sherry, the soils need to soak up and retain the winter rain to nurture the vine through the growing season.

There are three types of soil in or near Jerez, all good at retaining water. Around 90 per cent of all sherry vineyards are on chalky albariza, which is similar to the soils of Chablis and Champagne; then there are barros and arenas, which are more often used to grow grapes for sweet wines.

The Triangle’s climate and location close to the coast also has an impact on the sherry during the production stages. The salty sea breezes, especially notable in coastal Sanlucar, draw hot air out from the big, high-ceilinged warehouses in which the casks are stored, bringing humidity up from the ground, creating good conditions for ageing the sherry.

All these elements – the grape, the soil, the climate, the barrel – have to be ideal to produce a great sherry. Ultimately, however, it’s the sherry master who guides the process, continually tasting and assessing, and deciding how to best express the wine’s nature. Making sherry is as much art as science and nature.

Sherries in their best rendition deserve not only a place in granny’s liquor cabinet, but also their space on the menus of the world’s finest bars and restaurants. And if the passion for this unique taste of Spain continues to boom, that’s exactly where you will soon find them.