Theo Jansen is showing a group of eager journalists two of his mechanical Strandbeests at the Marina Bay Sands ArtScience Museum, explaining how they seduce each other and procreate with the deadpan earnestness of a BBC naturalist. “It seems like these two are seducing each other,†he says, referring to a video where the two Beests are courting and communicating. “In reality, they cannot reproduce physically and, in fact, they are seducing us (humans).â€

He elaborates: “These movies are on YouTube and, since then, many students are infected with Strandbeest ‘disease’. They start building their own Strandbeests and, without knowing it, they are used for reproduction. In this way, you could say that the seduction (via video sharing and social media) is a surviving tool.â€

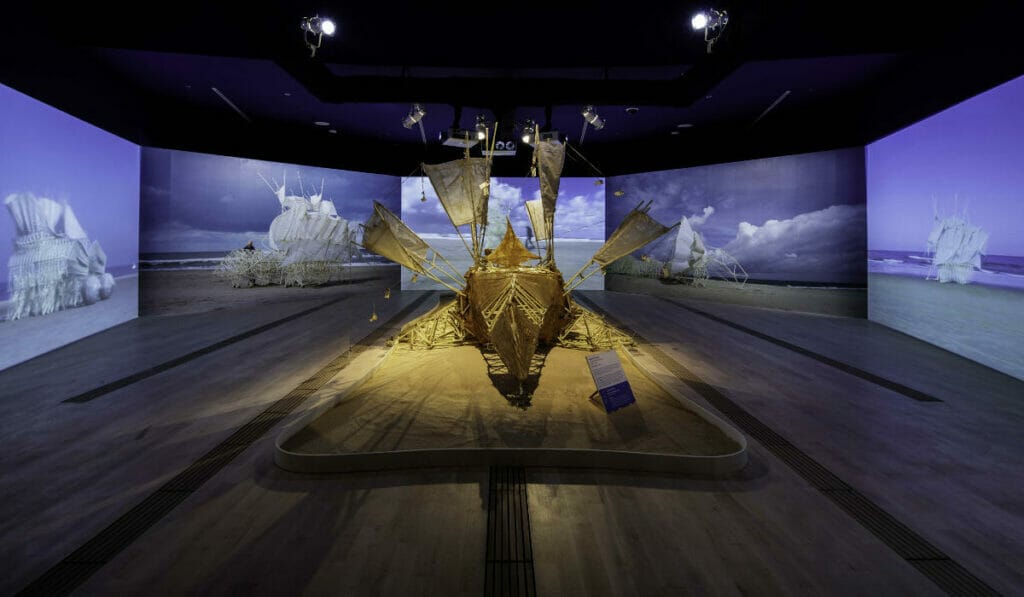

It would be easy to dismiss what the Dutch artist is saying about his creations as a bit of humour, tongue firmly in cheek, were it not for the fact that these kinetic sculptures seem to have taken lives of their own. So powerful and startlingly lifelike are these magnificent creatures, walking gracefully along Jansen’s favourite beach near Delft (short films on YouTube depicting this are constantly shared, and surface time and again on social media – the reproduction that Jansen speaks of) that one would be quite forgiven for almost imagining a beating heart in each of them.

Really, they are made from ordinary PVC piping, wood and fabric airfoil, powered by nothing more than wind, ingenuity and the power of the imagination. Jansen has gone so far as to accord his sculptures with complete biological life cycles, claiming that they are evolving into intelligent beings.

It is no coincidence, too, that watchmaker Audemars Piguet has seen a kindred spirit in Theo Jansen, with a partnership starting from Art Basel Miami back in 2014. This year, the maison has extended its support by bringing a retrospective of Jansen’s most famous creations to South-East Asia for the first time.

The worlds of art and watch have cited the alliance as an inspired pairing, with the watchmaker’s own spirit of innovation, craftsmanship and intelligence mirroring that of Jansen’s. The Strandbeests are a brilliant merging of science, art, engineering and performance, not unlike the maison’s timepieces.

“Theo came to us before the Audemars Piguet Art Commission was even established. It was the work that just preceded the establishment of the commission that helped us define what type of categories and approach we wanted to take. When you look at Theo’s work, the connections to what we do in watchmaking aren’t even metaphorical. They are literal and tangible. They are immediate,†says Michael Friedman, Historian at Audemars Piguet.

“He limits himself to a very strict number of resources and, just as a watchmaker does, uses very specific tools. He also has a very specific goal and function in mind, and he is constantly improving his work, wanting to better his craft and utilising his creations of today to help advance the creations of tomorrow. These are concepts that are very natural to the field of watchmaking.

“There’s an immense amount of care in every single process he makes. If one small aspect goes wrong, then the Strandbeest won’t function. This, again, is very much akin to watchmaking – the ability for a watch to function as it should means that every single component, whether that’s 120 or 640 components in a complicated watch, has to work as it should; otherwise, the entire system breaks down.â€

Friedman also sees the connection in character. “Being a little bit of an outlier, we consciously chose to keep doing things differently when others were adopting a mass production technology at the time,†he says. “We adopted some of the technology to getting the rudimentary work done but, when it came to actual watchmaking and finishing, we remained completely pure in that respect. We are edgy in terms of creativity – by 1910, we were already experimenting with form language, materials and dial design, totally different from the rest of the Swiss watch industry. That’s the mission of the company. It’s not all CEOs and marketing making critical decisions; it’s the watchmakers.

“So, on the mechanical side, we, of course, find great connections with Theo’s work in that regard, but then you also have the more artistic and philosophical side of the relationship.â€

The outlier in Theo Jansen has shot him to certain fame with even a cameo appearance in The Simpsons together with his Strandbeests. But his brilliance – and penchant for mischief – really began with the young artist (looking uncannily like Tom Verlaine of proto-punk band Television with his lanky frame and long hair) scaring his neighbourhood into thinking the handmade flying saucer that he launched into the air was real!

At his interview with a small group of journalists, the now 70-year-old cuts an elegant figure, standing ramrod straight as he strikes some cool, rock-and-roll type poses against his creations and graciously answering questions. Curiously, everyone at the table treats his Strandbeests as if they were living, breathing creatures.

“When I see that the animal has some potential, then I make more of them,†says Jansen on the creation of a herd. “I have five caterpillars on the beach right now – you can just see that they’re all slightly different and, from running matches, you can see which system works slightly better. If something breaks, you can make it better in another animal.

“It’s a constant evolution process. (They are) mutants, you can say. Some will survive, some don’t. The winning mutant gives me a lot of hope to continue. There’s usually an experiment of a few hours. The whole summer I’m on the beach but I anchor them at night and, in the morning, I can do experiments. It’s not (come to a point) yet where I can let them free because they may run away and then I must get them back to where I work. It’s not very practical yet where they can survive on their own,†he says without a hint of irony.

In describing the Beests’ incredible mobility, he says: “For now, there are very few animals that can walk sideways on the winds, so most of them walk with the wind. Once it’s gone, they wait till (the wind has) turned 180°, then they can come back. Logistically, it would be a bit hard to do because then I’d have to go 50km further on the beach to go everywhere and wait, and it might take a few weeks because the wind must turn 180°.

“They can wait there, of course, but they’re animals; they don’t care about time at all. But I care about time. I’m 70 now and might still work for 20 years at the most. I’m in a hurry to do all these experiments, and I cannot let myself go with all these funny things and go all the way there – 50km further.â€

Time is of the essence for Jansen and Friedman notes this as well. “Theo is also consciously playing with time,†he says. “He is in the process of an experiment with evolutionary biology, working under the guise of a creator in a way and introducing these species, seeing what works best and those best attributes of each Strandbeest will then evolve into the next Strandbeest. This playfulness and experimentation of time in a much broader sense is tangential category that interests us greatly.â€

Jansen is also frank about his choice of materials for the Strandbeests, dispelling any lofty motives of elevating the plastic tubes and piping. “I think it’s just laziness,†he says matter-of-factly. “The tubes were there, and they were cheap. I’m not so much of a person to go and shop and buy everything I need to do something. I’d rather work with something within 10m,†he laughs. “And I’m not too much of a scientist either, so I don’t go to the library to look up how things are solved. I’d rather work it out – I’m quite isolated, you could say.â€

In as much as the artist talks as if the Beests were alive, he is very much a pragmatist in the way he treats them. When asked if he gets attached to them, he is quick to reply: “Not as much as people.â€

“Of course, there is emotion,†he elaborates. “But I think the emotion could be compared to (how one feels about) a bike.†More laughter. “It’s a different emotion that I have compared with my dog or children. Its species is too far away from us. You can only feel something that has a similar brain. I can feel for a dog, for instance, but for something that’s just (made of ) sticks – no.â€

Jansen, however, is quite pleased with how his creatures have evolved. “My animals are still far away from artificial intelligence, because the number of bits is so small compared to real computers nowadays. Of course, if you give me another few million years, then the animals would be very intelligent.â€

How so? “Well, the brain is a very good weapon in survival. The brain is fed by our information and the sensors. Say, if the wind is too strong, the brain gets the information that it’s too strong, it decides to hammer themselves in to protect from blowing away. Those kinds of things are possible. They are not operational yet, but it works. It’s not a daily practice that they feel strong winds, or have a barometer where they can feel the drop in atmospheric pressure and predict a storm. It’s not there yet, but it could happen.â€

It’s not hard to imagine Jansen as the quintessential Renaissance man and Friedman agrees. “What we are interested in are the principles or concepts – complexity, precision, quest for accuracy, beauty, mechanical ingenuity, structure, and then objects with this type of temporal connection to it that you can experience time itself through his process as well as through you own engagement. It was an ultimate way to begin our art commission because of who Theo is as a man, artist, scientist and thinker – it was very inspiring for us as a company. Olivier Audemars, our Chairman, has gone on record to say, ‘We’re not in the process of collecting art at Audemars Piguet, but we are interested in learning from and being transformed by the artwork’.â€

Jansen himself is constantly transformed by his creations and is not beyond being awed by them himself. “You could say my base is fairy tales,†he says. “But everything I talk about is real. They’re all based on reality. I like the balance between imagination and reality because sometimes you can’t see what’s real and that’s why I like to fool people – it’s something that you really believe in for a moment that is true.

“That a man can make a new specimen? That’s a fairy tale. But the fairy tale can also be a bit true and I like that. It gets people a little bit confused.â€